In 1969, Norwegian artist Terje Brofos (better known as Hariton Pushwagner) locked himself inside a writer’s friend’s house and hallucinated a man named Mr Soft, who was driving a car. “Was he on LSD?” Rude question. You should shut your whorebag mouth. Yes, he was on LSD.

Three years and several misadventures later (near-homelessness in London, a hotel fire in Paris, and an arrest when trying to board a flight to Madeira walking on his hands and knees), Pushwagner became a parent. This—plus a soup of trauma from his own difficult childhood—inspired him to create a full-length comic about Mr Soft. This book, lost for a quarter of a century, finally saw publication in 2008.

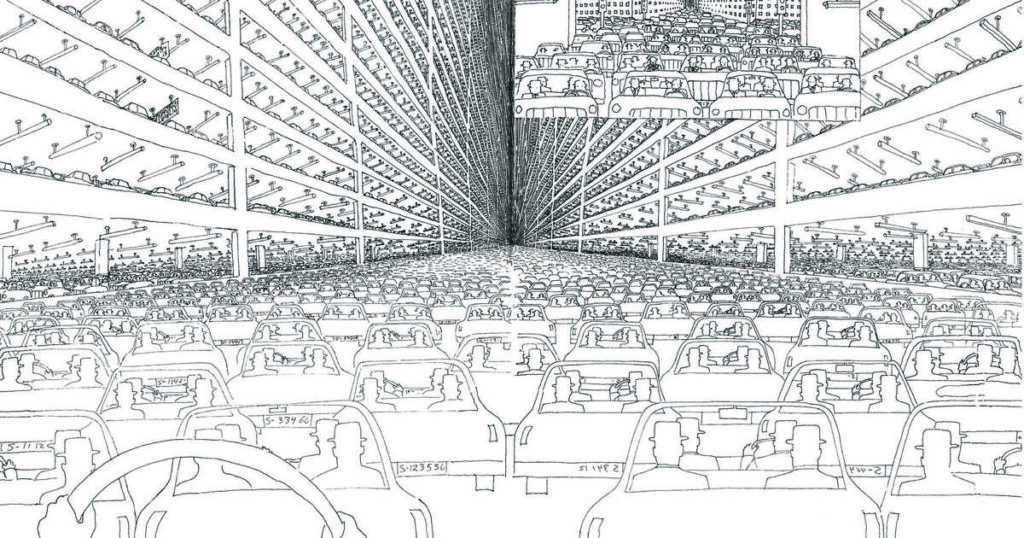

Mr Soft now lives in a bright, endless city. It’s a horrifying arcology of poured steel and concrete. Buildings swallowing the sky like abominable wallpaper, and strangely-eyelike windows peering down at the streets in obsessive contemplation. Even the sun has an eye. Soft City is familiar yet alien: it seems like a place for termites to live, not men.

The comic has no story and no characters. It shows Mr Soft going about his day in this urban insect hive. Like Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (an inspiration, I believe), it cuts out a twenty-four hour slice of time, and forces the reader to interpret it with no past or future. What yesterday could have led up to it? What tomorrow can come after it? Who knows. We can only dream. Pushwagner cuts away context like a cancer, making you stare at what’s in front of you until the eye bleeds.

I’ve long felt that the best setting for any work of dystopic fiction is right now. It’s a well-worn piece of Orwell lore that 1984 wasn’t written about the future but about Orwell’s current times (notably, 1984 is a rearrangement of 1948, the year the book was written). Whether or not that’s true, dystopic fiction loses its edge when it’s set in the future, which can seem very foreign and far away. I used to commute to work through snowdrifts of litter. When I visited rural China, and all the men had cigarettes sticking out of their mouths, like antennas to hell (my own country was the same two generations ago). People don’t care about the inhabitants of the future, not even when those inhabitants are their own future selves. They exist outside our moral circle. Pushwagner knows not alienate his humans by setting them in a far-off fairytale land we can ignore. He makes them alien for other reasons.

The men of Soft City are like clones or robots. They wake up at the same time, take their pills (there’s a “life” pill to wake them up, and with a matching “sleep” pill for the end of the day), have repetitive interactions with their wives and children, and then collectively commute to work in the beating unheart of the city.

Obviously, their jobs are a parody of useless corporate wagecucking (and their boss is like Glengarry Glen Ross’s Alec Baldwin after a frontal lobotomy), but their home lives are equally artificial. There’s no escape from the existential contrivance of life. Pushwagner loves the trick of showing Mr Soft enjoying some touchy-feely personal moment, like kissing his wife or playing with his baby son—then zooming out, so we can see the same thing happening in hundreds of other windows. It’s commodities, all the way down. This is one of those all-purpose satires that could be read as commentary on capitalism or communism. It depicts a failure mode, a Molochian trap. The early bird catches the worm, but not every bird can be early. When you get up early to beat the traffic, you shift the hour of peak traffic a little earlier, and if everyone’s doing that…

Mr Soft becomes impossible to regard as the main character, because he is like everyone else. He drives in a stagnant sea of cars, driven by indentikit humans that look like they rolled off a production line. We lose sight of him—a human sorites’ paradox. Occasionally someone does stand out in Soft City, but it’s always for bad reasons—like that person crying out “HELP!” as a baton-swinging officer pounds him into the asphalt. By the end of the book (which can be read in about an hour), we cannot even conceive that Mr Soft is a human being. He’s more like a molecule, propelled from place to place, but never alone, and never of his own will.

Anthropologist Robin Dunbar theorized that people can maintain effective social connections with just 150 people: everyone else overflows the bucket and becomes an “outgroup” that our brains regard suspiciously, as if they’re not quite human. (“They always screw the little guy“. In this sentence, “they” are the outgroup.) Who’s “in” or “out” of your Dunbar circle depends on context. Why is the relationship you have with your mother sacred? Because there’s just one of her. If you had 1,000 mothers, you wouldn’t feel any sort of connection to them, would forget their names, and wouldn’t even care enough to try to remember them. Soft City takes us on a similar journey. At first, Mr Soft is a human. One of us. By the end of the book, Dunbar’s Number has prevailed. He has been mashed and puree’d into exactly the black inhuman paste that Soft City thinks he is.

The minimalistic art means all objects look the same. People take pills to get through the day. The pills remind us of the cars. Everything is a hollowness: just a container for something else, lacking its own existence. Pushwagner sometimes uses mirrors to duplicate cars. This reduced his workload (there are literally thousands of cars), while adding to the sense of artificial sterility. In this society, a car is a shell for a driver. A cubical is a shell for a worker. A woman is a shell for a baby. It’s a world of cardboard boxes, which exist to hold other, smaller cardboard boxes.

Judged as a comic, Soft City is bleeding-edge alternative. You could call it outsider art. Pushwagner’s wobbly, fussy linework is easy to understand, challenging to interpret, and harder to love. His shapes don’t close. There are no colors or even shading, and no sense that his world would support them. There’s also a strong impression—and I think this was intended—that the drawings are missing something. Your senses grasp and hunger for something that isn’t there. It’s like an 80s videogame, where lush artwork has been brutally downsampled to 16 EVGA colors: you feel the missing hues. Everything is stripped down and function-based and the baby got thrown out with the bathwater a long time ago.

Pushwagner lived on the wrong side of the world to participate in the San Francisco “comix” scene. Had the cards fallen differently you could imagine Soft City serialized in Spiegelman/Mouty’s RAW anthologies, or Crumb-era Zap Comix. In 2008, it heavily evokes the “ugly on purpose” aesthetic of Adult Swim cartoons such as Superjail! Movies like Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs, and Jacques Tati’s Playtime draw from the same well, as do many books by JG Ballard. Conformity, corporatism, the bland ineffable horror of packing an image with cubicles and chairs and cars and people until it breaks the viewers mind like an overloaded conveyer belt.

Yes, the social commentary is shallow. Pushwagner isn’t the first person to dislike traffic jams and office cubicles and consumerism. Sometimes it approaches “I’m 14 and this is deep” territory. Like when we see a man dreaming of being a fighter pilot, which is later echoed by scenes of what the Soft City air force actually gets up to. (“Heil Hilton!”)

Other times, the naive “outsiderness” of Pushwagner’s art gives it emotional poignancy. It has something of the realness of a child opening his eyes and noticing the world—truly noticing—for the first time.

Most artists don’t manage social commentary on this level without a sense of smugness and intellectual superiority. I’m smart, unlike these dumb-dumbs. Banksy has never sat well with me: his shtick ultimately feels like a 4chan troll going “thank you for proving my point for me”. But the emotions here seem simple but real and earned.

This is because Soft City is also a mirror held up to the artist’s face. Pushwagner doesn’t exculpate himself from this society. The first living thing we see in the comic is not Mr Soft, but Mr Soft’s young child, who has an innocence that can’t and won’t last long. It’s one thing to live in a place like this. But what does it mean to have a baby in Soft City? Pushwagner had recently become a father, which meant he confronted that choice himself.

This also makes hard to understand. As I piece together fragments of Pushwagner’s life, I feel like I’m reading a half-mythical folklore figure, not a man. Living on the margins. Shredding his mind through drugs and outre experiences. Even the account that Soft City was “lost” for a time is curiously muddled. Pushwagner insists that his portfolio was stolen upon his 1979 return to Oslo, while biographer Petter Mejlaender says it was merely lost. Legal disputes were also involved. If he’d lived in America a few years earlier, we’d have called him a “beat”. As with someone like Robert Crumb, he was a weird man who inflicted deliberate damage upon his brain to become still weirder. Mr Soft lives a life of conformity. From what I know of Pushwagner, his own life was defined by non-conformity. Maybe in Mr Soft, he saw the Devil. Someone who made all the wrong choices in life. But it shows that the reverse of stupidity isn’t necessarily intelligence, Pushwagner was right to fear the horrific legibility of the modern age. But the polar alternative—radical freedom—isn’t so pleasant, either.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.